What Makes Art Psychedelic?

How LSD-fueled visions infiltrated rock posters, ads, and 'Sesame Street.'

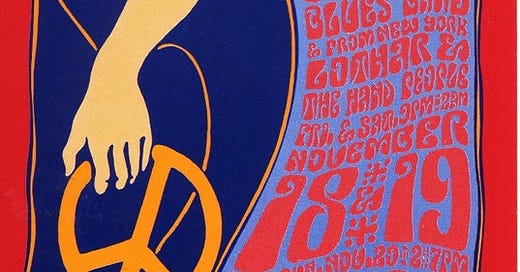

Wes Wilson’s Grateful Dead poster.

Close your eyes and picture “psychedelic art.” Chances are you’re seeing a bold color palette; natural figures and landscapes depicted askew, often with striking juxtapositions; or optical illusions that appear to move. Many of us know it when we see it, and can see it in our mind’s eye, even if we’ve never broken down its elements or considered how they came to be. Even if—and this is key—we’ve never even considered dropping acid or partaking of shrooms ourselves.

Art inspired by psychedelic experiences may date back to the Paleolithic era: Some researchers believe that certain patterns spotted in cave paintings, like dots and wavy lines, indicate that their creators were on something hallucinogenic. And in the 1950s, French poet and artist Henri Michaux produced a sketch series depicting his visions while on mescaline. But like psychedelic rock, psychedelic art is inextricably linked to the 1960s counterculture in America, when hallucinogens and hippies went hand-in-hand. These works were either inspired by psychedelic experience, or, at least, mimicked it. The idea was to depict one’s inner landscape as seen while tripping. As a result, most of us had an idea of what we thought a psychedelic experience would look like, even if we’d never had one. In fact, we use the word “trippy” to describe this aesthetic quite broadly.

Surrealist René Magritte’s “The Double Secret.”

Psychedelic art followed as a natural descendant of surrealism, which developed after World War I and concerned itself with the unconscious mind, seeking to unearth deep-seated creativity through nonsensical combinations and, often, the depiction of the artist’s dreams. One of psychedelic art’s earliest manifestations came from the experiments of Los Angeles psychiatrist Oscar Janiger in the 1950s. Janiger famously introduced actor Cary Grant to psychedelics, but he also did research on their effects on creativity, including a study in which he had artists paint a subject of their choosing while sober, and then several more times throughout an LSD trip. In one depiction online via LiveScience, which is believed to be from the study, the artist’s drawings grow more abstract and interesting as the experience progresses. Of course, most psychedelic art isn’t necessarily produced while the artist is high, but rather depicts their memory of a previous experience or was inspired by a vision during a trip. But Janiger’s experiment led the way toward the idea that psychedelic experiences are uniquely worthy of artistic expression.

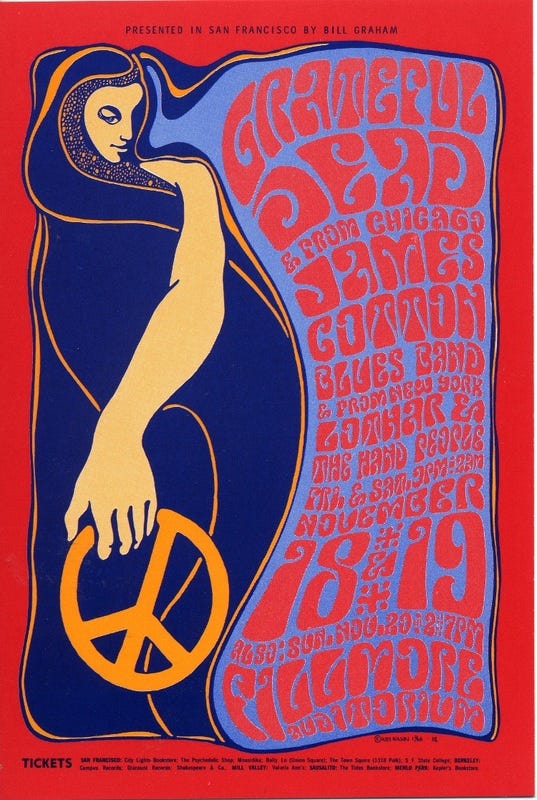

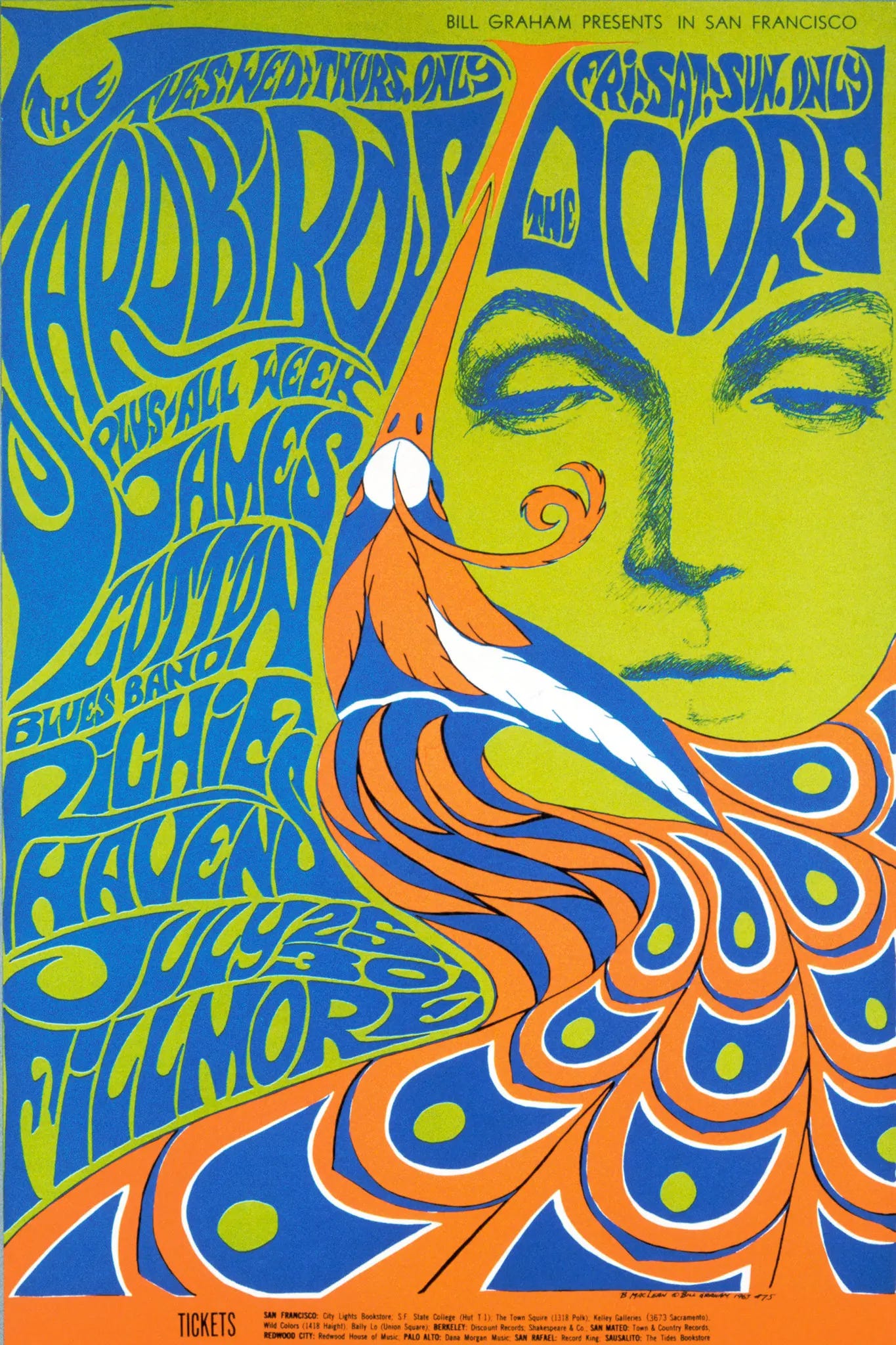

Ultimately, psychedelic art found its footing in the realm of 1960s concert posters by artists such as Rick Griffin, Bonnie MacLean, Victor Moscoso, Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, and Wes Wilson. Their fantastical, striking images, highly influenced by Pop Art and Art Nouveau, sometimes appeared to be ripped from terrible nightmares, or very bad trips—an eyeball with wings and tentacles, for instance. Other times, they presented a soft, technicolor beauty—a woman’s face caressed by peacock-like feathers—equally likely to appear on a very pleasant trip. (Peacocks were very big in this movement.) Communication of the actual concert information was beside the point, given the highly stylized lettering that bent and warped in service to the aesthetic. No one wanted to harsh anyone’s mellow with cold, hard facts like concert times and locations or even band names.

A Bonnie MacLean concert poster.

The posters were one of the most easily identifiable ways that psychedelics infiltrated mainstream popular culture. If you lived in, say, San Francisco, you were bound to catch a glimpse of this aesthetic, and come to understand what it represented, even if you had no idea what LSD and shrooms were. Soon the look spread to the center of pop culture, appearing everywhere from ads to Sesame Street. Naturally, this move toward the mainstream marked the look as square, and by the mid-‘70s it began to fade from prominence.

From the vantage point of today, we can see how distinctive this visual style is; it represents 1960s culture so unmistakably you can almost smell the pachouli and hear the Hendrix.