A Brief History of Psychedelics in Pop Culture

From Cary Grant's culture-shifting LSD trips to the War on Drugs, '90s rave culture, Harry Styles, Kacey Musgraves, and Lil Nas X.

There’s something transformative about learning the story of Cary Grant and LSD.

If you grew up during or after the 1980s War on Drugs, the time when we all came to understand that any illegal drug would fry your brain like an egg, the Cary Grant psychedelics tale shifts your entire perspective, is nothing short of an enlightenment moment. There’s something magical about the combination of this dapper icon of straight-laced masculinity (look at him up there!), coupled with this hippie drug, plus this dream of a mainstream media that was totally stoked about the possibility that mind-altering substances could be good. It’s when you understand: The 1950s were way more complicated and interesting than I was led to believe.

The story goes like this. In the ‘50s, Cary Grant, who was a combination of George Clooney and Jon Hamm and could wear the hell out of a suit, had his share of mental health challenges—despite, or perhaps because of, his charmed career. He’d had a Dickensian childhood in England, growing up poor, with his mother institutionalized; he pulled himself out of poverty by learning acrobatics and becoming a vaudeville performer. Due to the right place and the right time and his dimpled chin, he made the transition to actor and then Old Hollywood movie star. His difficult upbringing continued to haunt him—and his relationships—even when he appeared to have it all. “Everyone wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant,” he said. “I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be until finally I became that person. Or he became me. Or we met at some point."

It seems perhaps the meeting didn’t go as hoped, and off to therapy he went. His particular therapist, Dr. Mortimer Hartman, used LSD in combination with more traditional analysis. He would give Grant a prescribed dose, put on some music, then help Grant work through his feelings as he tripped. It freed Grant to dip into places he couldn’t go otherwise. “LSD permits you to fly apart,” Grant said. “I got clearer and clearer. Your subconscious takes over when you take it, and you become free of the usual discipline you impose upon yourself. I forced myself through the realization that I loved my parents and forgave them for what they didn’t know. I became happier for it, and the insights I gained dispelled many of the fears I had prior to that time.”

What’s wild to us now is that Grant talked freely of this in interviews, extolling its virtues the way celebrities might, in more recent times, talk about a diet or exercise routine or supplement. The most famous of these interviews was in none other than Good Housekeeping, that bastion of housewife tips. The magazine was 100 percent on board, celebrating that he was “courageously permitting himself to be one of the subjects of a psychiatric experiment with a drug that eventually may become an important tool in psychotherapy.” There’s even a story, though an unsubstantiated one, that Timothy Leary, the man who brought LSD research to the next level and then crashed it straight into the Nixon law-and-order era, was inspired to pursue work in psychedelics by reading that exact article.

Even if it’s false, there’s an emotional truth in that Grant-Leary connection. They were twin forces in bringing LSD to the masses. In fact many in Hollywood—and presumably across America—were first inspired to try it when they learned of Grant’s endorsement. “I figured if it was good enough for Cary Grant, it was good enough for me,” recalled Judy Balaban, the daughter of Paramount president Barney Balaban. Leary would pick up the cause from there, and then blow it all to pieces. More on that in a minute.

For those of us who grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, Grant’s tale of LSD enlightenment is not what we’ve tended to picture when it comes to drugs and Hollywood. What our brains go to is the dark and tragic stories of addiction and overdose, or of rehab and redemption. Coke, heroin, speed. This is the lens through which we interpreted the LSD craze of the past. But the 1950s and ‘60s were, truly, a different time when it came to psychedelics. Mass media, beyond Good Housekeeping, was celebrating them as a possible panacea, cheering researchers on. Time magazine, in an article headlined “Dream Stuff,” reported in 1954 that “LSD 25, while it has no direct curative powers, can be of great benefit to mental patients.” Life magazine ran an adulatory photo essay in 1957 with the cover line “The Discovery of Mushrooms that Cause Strange Visions.” Time profiled celebrities who took LSD under doctors’ supervision in 1960.

Psychedelics were on the verge of mainstream.

Then things took a turn. LSD became so popular that people began taking it outside doctors’ offices, having bad trips sometimes, and fueling a media backlash. Then Dr. Timothy Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert began running experiments with LSD at Harvard University that got out of hand and made administrators nervous. The researchers held party-like LSD sessions, and did LSD with their student subjects, which seemed like iffy scientific method. Rumors circulated about undergrads making money by smuggling LSD. Leary and Alpert were fired and launched their own organization, the International Federation of Internal Freedom. Leary took it upon himself to serve as psychedelics’ spokesman, urging everyone to “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

The media’s love affair with psychedelics began to devolve. Cosmopolitan reported in a 1963 story that they might not be such a cure-all, with doctors quoted bemoaning the ways that Hollywood had been proselytizing about them. Life magazine did an about-face on LSD in 1966 with a cover story about “the exploding threat of the mind drug that got out of control,” calling it “turmoil in a capsule.” Leary became the perfect target for President Nixon in the 1970s, a raucous remnant of the hippie age that the politician could make an example of (especially after Leary broke out of prison, where he was serving a sentence for marijuana possession). Psychedelics, meanwhile, were outlawed and placed on “schedule 1,” the list of drugs with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” along with, for instance, heroin.

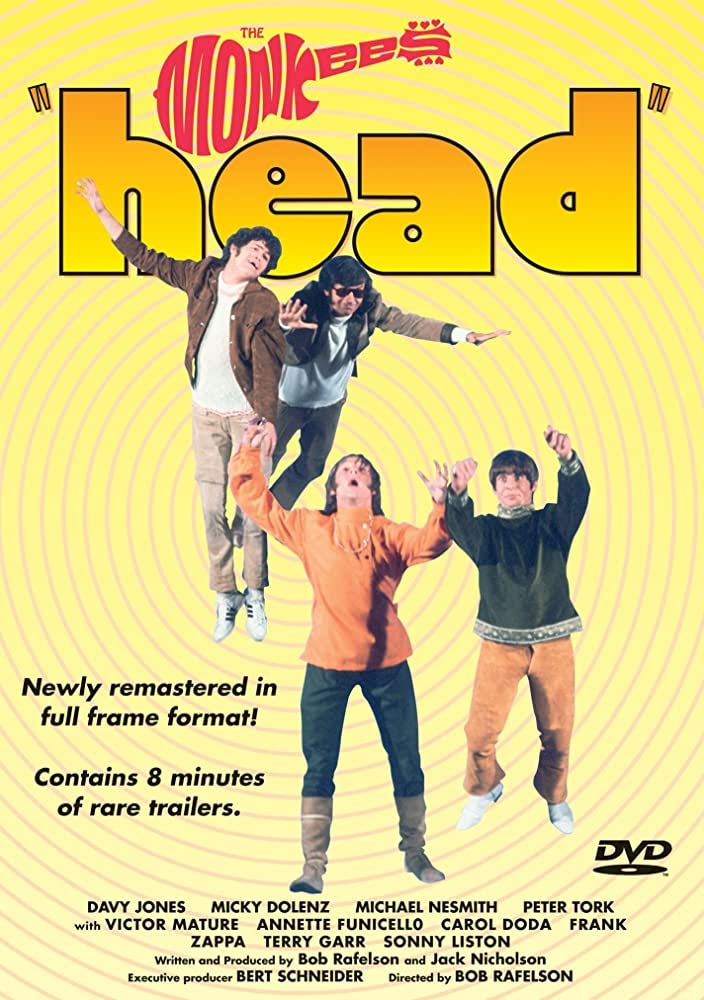

In the meantime, however, psychedelics had seeped into our pop culture. The “LSD film” had become its own subgenre, including the likes of Roger Corman’s The Trip, Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, and Otto Preminger’s Skidoo. Psychedelics infused rock music, from the Beatles to the Grateful Dead. And if you think psychedelics didn’t find their way to television, you’ve never watched The Monkees or their movie Head (co-written by Jack Nicholson!).

But those became cultural relics as time passed, an aesthetic we didn’t totally understand if we hadn’t lived through that time and experienced LSD ourselves. And so it was that we entered the 1980s with a totally altered cultural memory of psychedelics’ journey from panacea to schedule 1, brain-frying evil. Cary Grant, reduced to his pop cultural essence in retrospect, was the clever, debonair, suit-wearing guy trying to outrun a crop-duster in North by Northwest or romancing Deborah Kerr on a cruise ship in An Affair to Remember, not a countercultural hero. LSD became a Deadhead punchline or a dirty little secret (remember figuring out that the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was more about its acronym than a bedazzled girl?). We absorbed the gestalt of psychedelic culture from a certain time—sitars, jam bands, kaleidoscopic colors—and stopped questioning how that came to be.

In the decades since the psychedelic heyday, new forms of the drugs (or close cousins) have surfaced, and, tellingly, inspired subcultures to spring up around them. And those subcultures have occasionally gone mainstream, highlighting the inextricable link between psychedelics’ creative powers and pop culture. Think, for instance, of the rave culture of the 1990s, where MDMA, LSD, and ketamine mixed with electronic dance music at a secret location, with ravers wielding glow sticks, pacifiers, and feather boas. It hit the big screen with the 1999 Doug Liman film Go, starring Sarah Polley and Katie Holmes, and EDM became a lasting force in pop music.

Now, another psychedelic renaissance is upon us, and we have a chance to do it right this time. Widespread acceptance would allow more people to get the real help these drugs can offer when it comes to PTSD, depression, anxiety, and addiction—not to mention an express ramp to spiritually enlightening experiences. Serious scientists are doing serious studies that show remarkable results. Celebrities are once again talking openly about their transformative psychedelic experiences, including Kristen Bell, Harry Styles, and Miley Cyrus. Lil Nas X and Kacey Musgraves have acknowledged psychedelics’ influence on their recent music.

Psychedelics are going mainstream again, in a way they haven't been since Cary Grant’s LSD trips got the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. What's going to happen this time around? A graceful accommodation into the American establishment, like yoga, mindfulness, and even cannabis? Another backlash, moral panic, and prohibition? A third way, where psychedelics become widespread and still exert a radical influence?

The future will be determined by how the public perceives this new wave of psychedelics. So now is the time to look back at the history of psychedelics and pop culture, and analyze pop culture's current reaction to the new wave. We’ll be tracking it all here in Culture Trip. I’ll bring my background as a cultural critic and historian—as well as my experience as a Buddhist, spiritual seeker, and believer in psychedelics’ potential—to serve as your guide through psychedelic culture past, present and future. We’ll explore psychedelic music, the history of the hippie movement, and ‘90s rave culture; we’ll track current media coverage, books, and celebrity interviews; we’ll learn how psychedelics are affecting sports and the arts, and how they intersect with race and class.

And here, we’ll remember Cary Grant not for his suits or his mid-Atlantic accent or his dimpled chin, but for his willingness to take LSD, fly apart, put himself back together again, and tell Good Housekeeping all about it.