JFK, LSD, and the Limits of Enlightenment

A sensational story about JFK, LSD, infidelity, and murder shows us the limits of our favorite means of spiritual seeking.

There is a sensational story about JFK, a mistress, LSD, and murder that is almost certainly not true. But the fact that it exists, and persists, tells us something important.

It goes like this: While president, JFK had an affair with Mary Pinchot Meyer, an artist and a friend of his wife, Jackie Kennedy. Pinchot Meyer was divorced from a CIA official named Cord Meyer. Around this time, she went to see Timothy Leary, the former Harvard psychology professor-turned-LSD evangelist, to learn how to facilitate LSD sessions. She told him, Leary said, that “powerful men” in Washington, D.C., were plotting to “use drugs for warfare, for espionage, for brainwashing,” but that she and some other influential women wanted to use them “for peace, not war” by turning on major players and leading them to enlightenment.

But soon Pinchot Meyer was warning Leary that they were both in trouble because one of the women she’d recruited for her plan “snitched.” And then JFK was assassinated in November 1963. Soon after that, Leary claimed, he got a desperate call from Pinchot Meyer, in which she said, "They couldn't control him anymore. He was changing too fast ... They've covered everything up.”

It wasn’t until Leary read a National Enquirer story in 1976, in which journalist James Truitt revealed the Pinchot Meyer/JFK affair and said that the two had smoked marijuana together in the White House that Leary jumped to the conclusion that when she had called him, she was talking about having turned the president on to LSD. At this point Leary also learned that Pinchot Meyer had been murdered on October 12, 1964, while walking the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath alone. She was shot at close range in the temple and the back. Her murder was never solved.

The affair seems to be true, and she was definitely murdered. But it’s unclear how much of the middle part—that is, the Leary and LSD part—is true, if any. This story doesn’t appear in any form in Leary’s extensive writings until his 1983 memoir Flashbacks. Leary’s and Pinchot Meyer’s biographers believe they met, but haven’t found any proof of the rest.

But it’s a truly cinematic tale, and as LSD’s foremost advocate, he had good reason to fill in the details as he did.

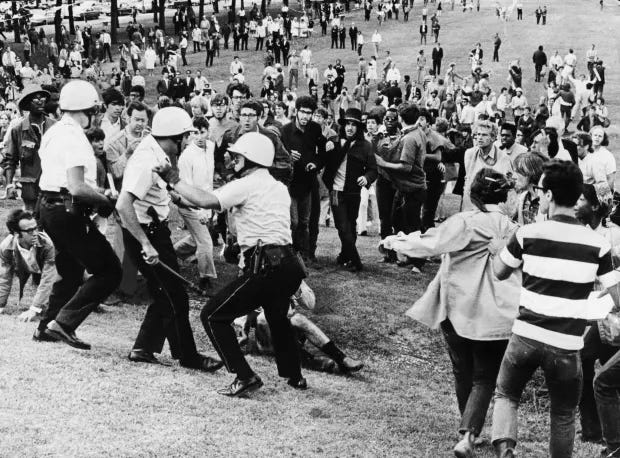

There’s another story that shares some major themes with this one, but had much more serious real-life implications. In the chaotic lead-up to the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago that erupted in violence between police and anti-war protesters, the activist group known as the Yippies, led by Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin with a decidedly performance-art bent, put out a bulletin that they were sending “super-hot” hippie girls to seduce delegates and give them LSD, along with hippie “studs” to similarly seduce the delegates’ wives and daughters. Mayor Richard Daley took them at their word and freaked out accordingly, which at least helped to contribute to a massive overreaction on the part of the city. CBS News correspondent Dan Rather was roughed up on camera, nearly 700 people were arrested, more than 600 were treated for injuries, 400 suffered from tear gas exposure, and more than 100 went to the hospital, while nearly 200 police officers were injured. There is no record of delegates being seduced into using LSD.

Why are these stories so appealing? Why do they stick in the imagination, even help to incite real violence, despite being so obviously absurd?

The very alluring common thread: Sex and psychedelics can save the world, and the only problem is that we can’t get them to the right people! The JFK story has an extra dose of assassination conspiracy theory, compounded by poor Mary Pinchot Meyer’s death. The idea that they were both killed because LSD was too powerful … my god, what a narrative.

The convention story was the opposite in many ways—not whispered and pieced together, but literally announced. But it seems to have hit Daley like a conspiracy theory, like his worst nightmare of what the protesters might be up to. He clearly found it threatening, and this helped to cause a massive blunder of historic proportions.

Both stories have a specifically political bent that makes them extra intriguing, especially in a time of stark polarization—the ‘60s, not unlike now. Could one mushroom trip turn an uptight official into a bleeding-heart liberal preaching peace and love?

There have been similar fantasies about meditation’s potential to change the world. In the ‘60s Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of Transcendental Meditation, suggested that if a mere 1 percent of the world’s population practiced TM, it would have a discernible positive effect on collective consciousness. “He believed that it is the accumulation of stress in the collective consciousness that leads society into war,” explain Dr. Miguel Farias and Catherine Wikholm in their illuminating book The Buddha Pill: Can Meditation Change You?

An ambitious 1993 experiment in Washington, D.C., even set out to prove this hypothesis. Four thousand TM practitioners moved into apartment buildings in the city for two months of meditation focused on one goal: to reduce the crime rate in the city by 20 percent. They meditated twice daily, from 7:30 a.m. to noon, and then from 5 to 7 p.m. It cost $4.2 million. When the results were published in 1999, they showed that violent crimes fell by 23.3 percent. But there was one massive caveat: While rapes and assaults had decreased compared with the same period the previous year, murders had actually increased. The original result was swayed by a decision to eliminate the “murder” portion of the statistics because a gunman had fired at a swimming pool full of children during this time. It was deemed a “statistical outlier,” which … doesn’t seem right, given the extreme thesis the study was trying to prove. If meditation decreases violent crime in its orbit, it decreases violent crime in its orbit. You can’t pick and choose which violent crime it decreases. To compound the lack of real results, robberies hadn’t decreased, either. No further studies have been undertaken at this level.

I want to believe that both psychedelics and meditation are as powerful as these stories and studies postulate. I have personally found them to be transformative. In my own reporting on psychedelics, they have been cited as possible panaceas for both our mental health and environmental crises. Studies have shown them to be promising in treatment of PTSD, anxiety, and depression, and more grandly, many advocates believe that psychedelics’ ability to help us see the interconnectedness of all beings could nudge us toward more meaningful action to stop global warming. I remember the first time someone suggested this to me, the a-ha feeling: Oh, maybe this could solve all of our problems. Mushrooms in every pot!

But it’s also worth being cautious when it comes to the idea that a night of fun, full of sex and psychedelics, could be the answer to it all. It’s impossible, for instance, to know the real psychological—and political—implications of someone tripping when they are not intentionally taking psychedelics, when they do not necessarily have good intentions or a sound moral compass. What if they just had a bad trip? What if the trip just reinforced all of their terrible ideas?

In many ways, particularly from a complicated 2024 perspective, all I can say is: If only it were as easy as sending in hot hippies to seduce and dose everybody. If only we could stop mass shootings by sending in a few thousand people to meditate. Alas, I am skeptical of such easy solutions, even if they’re not so easy. The harder answer is that we all have to do the hard work. If mushrooms or LSD or meditation helps you get to the place where you can work to make a difference, so be it. Let’s all do our part, however hard it might be, using whatever means get us there.

this is really interesting. I never knew this story!

Throughout my book I speak of my friendship with Ted Swager, a trance medium and protege of Arthur Ford (of Bishop Pike fame). Ted gave readings for many influential clients, including Congress people and even a future President. One story sticks out.

JFK & Mary Pinchot Meyer, a Georgetown socialite and artist, were longtime lovers. She was mysteriously murdered execution style (by the CIA?). The police never solved the crime. As a last result, her sister Tony & brother-in-law Ben Bradley (editor of the Wash. Post) had a trance session with Ted to seek information about the murder. It made national news.

Did Ted actually speak to the dead or simply tap into his unconsciousness? You’ll be surprised to discover his analysis of the meeting.

You can read about the amazing session in “Exploring the Paranormal” (Eerdmans).