How Timothy Leary's Pot Arrest Led to the War on Drugs

The original high priest of '60s psychedelics fought his marijuana arrest all the way to the Supreme Court and won—but also helped inspire federal criminalization of both cannabis and psychedelics.

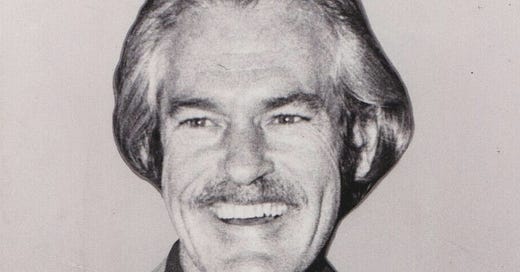

Dr. Timothy Leary in 1970.

America’s most notorious advocate for psychedelic drugs in the 1960s, Timothy Leary, faced off with the federal government over a pot arrest in 1969 and won. But the victory would soon turn into a major, lasting defeat for both psychedelics and marijuana in the United States, one we’ve only recently begun to undo.

It started when Leary went on a trip—a literal one—from New York to Mexico with his daughter, son, and two other people. They drove, and were turned away at the Mexican border. When they returned back over the International Bridge into Texas, a customs officer searched them and discovered marijuana in the car and on Leary’s daughter. Leary fought the charges, which were brought under the federal “Marihuana Tax Act.”

The act made cannabis possession illegal through the roundabout means of an excise tax, which, mind-blowingly enough, required an actual form to be filled out. Leary’s lawyers argued that this violated the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination, essentially making people out themselves as having pot so they could comply with the law. In May 1969, the Supreme Court agreed that this violated the constitution.

Leary had won the battle, but he would soon lose the war for everyone, for decades to come. The now-unenforceable Marihuana Tax Act was repealed by Congress a year later in the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. The new law established the category of “Schedule I Drugs,” which are classified by the government as the most dangerous, with no accepted medical uses and a high potential for abuse. And it put psychedelics and pot into that category alongside heroin and Quaaludes—even though we know now, and to some extent knew then, that both psychedelics and pot had potential medical uses.

By the time of his Supreme Court pot case, Dr. Timothy Leary was already infamous for his experiments with psychedelics at Harvard. As I’ve discussed here before, Leary got a bit too free with his LSD for administrators’ tastes, holding some LSD sessions with students that looked more like parties, and doing the LSD alongside his subjects. He and his associate Dr. Richard Alpert were fired in 1963, and they switched from an academic approach to a quasi-religious approach, founding the International Federation of Internal Freedom and the League for Spiritual Discovery. Leary became famous for his edict to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

The Neo-American Church seal.

Relatedly, Leary’s lawyers first defended him against the pot charges from the Mexican border incident using a religious freedom defense. They based this approach on the Native American Church’s 1964 California State Supreme Court victory, in which the judges ruled that the group could use peyote as a sacrament in religious ceremonies. Leary had since been citing this case himself when promoting the idea that psychedelic users should form their own “official” religion and thus make a play for protected use of the substances. Arthur Kleps, who did psychedelics with Leary at Leary’s famous estate in Millbrook, New York, actually did this, founding the Neo-American Church in the mid-1960s. (Official motto: “Victory over horseshit!”) Leary’s pot charges seemed to provide an opportunity to test the idea of religious protection for substances, but his lawyers abandoned this defense when it didn’t work in the lower courts. “The danger is too great, especially to the youth of the nation, at a time when psychedelic experience, ‘turn on,’ is the ‘in’ thing to so many, for this court to yield to the argument that the use of marihuana for so-called religious purposes should be permitted under the Free Exercise Clause,” the Fifth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in 1967. “We will not, therefore, subscribe to the dangerous doctrine that the free exercise of religion accords an unlimited freedom to violate the laws of the land relative to marihuana.”

The tone of that ruling foreshadows where this idea of legalizing drugs—for “religious” or any other purposes—was heading. The moral panic was about to boil over, leading to the highest-level federal criminalization of the two main hippie drugs, marijuana and psychedelics.

Cannabis, it’s worth noting, had been legal at the beginning of the 20th century. As of 1906, the only regulation was that cannabis products had to be labeled. Though some states began to place legal restrictions on it in the 1910s, the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, the law under which Leary was charged, was the first federal regulation. Once that was deemed unconstitutional by Leary’s Supreme Court case, the Nixon administration urged congressional action, and thus we got the Controlled Substances Act.

The 1980s “War on Drugs” followed directly, allowing for mass incarceration of drug offenders and the total demonization of all drugs for Gen Xers and Millennials who grew up in the “Just Say No”/”This Is Your Brain on Drugs” Era. This began to relax a bit in the 1990s, when California made marijuana legal for medical use and opened minds to a long-dormant possibility: Maybe some of these substances were helpful in some ways. By 2012, a number of states had followed suit, and Colorado and Washington became the first to make marijuana for recreational use as well. Now, 23 states have legalized recreational use, along with D.C. and Guam.

Now, according to a Pew survey from last year, Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of marijuana legalization. A whopping 88 percent of respondents said it should be legal in some capacity, with 59 percent in favor of recreational purposes as well as medical. Those who are 75 and older were the least likely to say it should be legal, which indicates that younger generations may normalize it in the decades to come, with a heavy emphasis on the social justice and job creation aspects of legalization.

While psychedelics face their own specific legalization challenges, two states, Oregon and Colorado, have acted to legalize and regulate them, while several other states are considering legislation, studying medical use, and reducing penalties. Some of Leary’s vision may still come to pass—and we may not even have to start our own religions for it to happen.