Psychedelic Movie History in Three Scenes

Film historian Saul Austerlitz joins me to analyze key moments in 'Easy Rider,' 'Knocked Up,' and 'Midsommar.'

We’ve talked a fair amount here about recent psychedelic scenes, which seem to mainly show up in television series these days, like Beef, Ted Lasso, and Nine Perfect Strangers. In these contexts, we’ve seen characters reconcile against all odds, bring their hopeless soccer teams to surprising victories, and dose other characters with psychedelics against their wills for not-terribly-clear reasons. (If a guru is so interested in putting psychedelics in her guests’ smoothies, why not just offer a proper psilocybin retreat?)

But psychedelics have been showing up in movies for far longer, dating back to the explosion in mushroom and LSD use in the 1960s (longer if you count psychedelic visuals in Disney movies like Alice in Wonderland, Dumbo, and Fantasia). Here, we’re going to look at three of the best psychedelic scenes spanning the last 50-plus years in film, each of which represents its own unique time in social history, movie history, and psychedelic history. To help with this task, I’ve enlisted my friend and colleague Saul Austerlitz, a film historian whose book about the movie Anchorman, Kind of a Big Deal, is out now. He also has a Substack called Hope in the Dark that I recommend. I’ll break down the psychedelics, while he’ll give us some film context and analysis.

Easy Rider (1969):

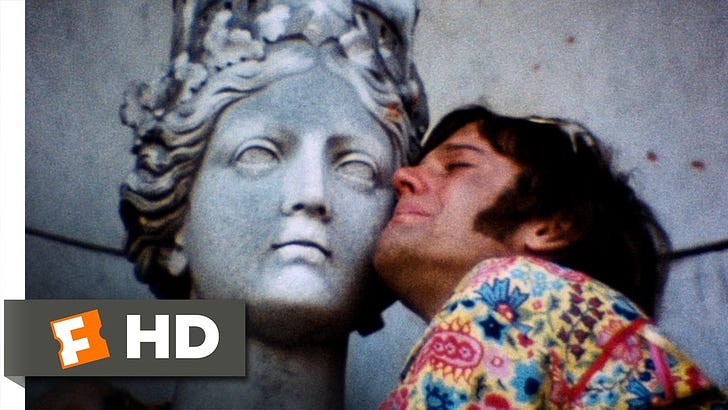

Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper play a couple of (relatively) long-haired motorcyclists riding through the American South with the cash from a cocaine deal, finding that the locals are not terribly welcoming of their kind along the way. In this scene, on a stop in New Orleans, they’ve just attended a Mardi Gras parade in town, then retired to a cemetery to drop some acid (along with some alcohol and pot). This scene is what has always stuck with me most from this film (along with Fonda’s leather jacket emblazoned with an American flag, heavy with symbolism). There was no clearer way to delineate countercultural youths from the squares than to show them doing LSD. And this seems like a fairly reasonable depiction of a trip in these circumstances: the way it comes in flashes, the intense emotions that feel a little scary because of the lack of control, but not threatening in a way that you worry for the characters. The Christian overtones of the experience make sense for the graveyard setting while also commenting on America’s religiosity; Christianity is so ingrained in these young adults that it naturally comes out in this situation, but combining it with drugs and sex in this way undercuts the strong association between piousness and respectability. —Jennifer

Easy Rider is a movie about the stalling out of the American Dream somewhere on the endless highways that ring the country. It is about two motorcyclists headed east, toward Florida, Manifest Destiny in reverse. And this graveyard sequence, one of the movie’s most famous, mashes together the erotic, the religious, and the natural. Fonda and Hopper sit together with their girlfriends in a cemetery, Fonda pale and glamorous as ever, Hopper scuzzy, lank-haired, vaguely Native American in his fringed leather jacket and matching headband. Fonda deposits a tab of LSD under his girlfriend’s tongue, and the moment is meant to evoke images of communion. This is our new mass, and as the two couples make out, the images alter, the editing speeding up. We hear talk of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, and the camera spins, spirals, restless. One recurring image shows a marble mausoleum with a busted panel, and a tree seeming to grow in the empty space. We are witnessing a resurrection of our own, prompted by acid, a rebirth in which Fonda crouches in a Pieta-like pose in the arms of a marble statue. In a land of death, we are reborn. —Saul

Knocked Up (2007):

Slacker/stoner Ben (Seth Rogen) and Type A news producer Alison (Katherine Heigl) have a one-night stand that results in her pregnancy; panic and lifestyle clashes ensue before they fall in love. Here, Ben has run off to Vegas with his married best friend, Pete (Paul Rudd), after Pete had a fight with his wife. The two get high on mushrooms and go to a Cirque de Soleil performance—not the best choice—then return to the relative quiet of their hotel room to wait out their trip. There, they have a pretty great discussion about love—Pete can’t accept his wife’s love, Ben wants Alison’s love—and also the nature of chairs. I love this scene’s combination of humor, vulnerability, and just the kinds of things you say when you’re high, simultaneously dumb and a possible subject of a philosophy PhD. thesis. (“It’s weird that chairs even exist when you’re not sitting on them.”) This moment marks a major turning point in the narrative, but it doesn’t feel like deus ex psychedelia to me; it seems plausible to me that these men would have a hard time feeling their feelings under normal circumstances, and that the mushrooms could help them have a genuine talk that gets them unstuck, exactly the result many psychonauts seek. —Jennifer

Paul Rudd and Seth Rogen have magnificent chemistry in this movie. (It’s a shame this clip doesn’t include the bit where Rudd absolutely butchers a famous line from Swingers en route to their Vegas vacation.) But here they are in their hotel room, and Ben is depressed, and Pete is manic. “There are five different types of chairs in this hotel room,” Pete announces, having dragged them all next to the bed where Ben lies. “The tall one’s gawking at me,” Ben observes of the chairs, “and the short one’s being very droll.” Ben and Pete’s bromance has hijacked the film, pulling them out of Los Angeles and away from their personal lives, but the drugs remind them of what they are missing. Rudd is an exceptional performer in nearly everything he does, but here he touches a place of profound self-loathing and confusion that speaks to Judd Apatow’s desire to commingle comedy and emotional nuance. “Do you ever wonder how somebody could even like you?” Pete wonders. He finds that he needs to switch chairs, crawling into a fetal position (echoes of Fonda in Easy Rider) as Ben rails at him. Ben craves the same love that Pete has turned his back on, and the scene is Apatow at his best: hilarious and also deeply heartfelt. —Saul

Midsommar (2019):

This folk horror film follows a young, troubled American couple played by Florence Pugh and Jack Reynor, who go to Sweden for a mid-summer festival but end up involved in a creepy pagan cult. In this scene, Pugh’s character, Dani, takes mushrooms offered by a cult member when they arrive at the commune and has a bad trip featuring her dead family; her bipolar sister killed herself and their parents. In this context, we have to see Dani’s trip the way she does, to understand why it’s so frightening and how it’s connected to her trauma, and this does the trick without going too overboard. She’s absolutely not in the best headspace to be doing psychedelics, especially in this environment full of strangers and a forest to get lost in, and this sequence reflects that. While one of psychedelics’ major benefits is processing trauma, that’s only with a qualified guide and a lot of therapeutic preparation and processing. The scene also sets up the way that drugs will continue to play a role in the plot in increasingly dark ways, leading up to the shocking final scene. —Jennifer

I just saw Ari Aster’s new film Beau Is Afraid, and while it is not quite as streamlined as Midsommar, it serves as a reminder of how good Aster is at unsettling viewers by inserting them deeply into the mental worlds of his characters. There is the anxious, hallucinating Beau, the world crumbling around his hunched shoulders; here it is Florence Pugh’s Dani, who glances down at her fingers during a trip and sees grass growing out of the back of her hand. Dani lurches to her feet and dashes away from her friends, and the camera follows her from behind, concentrating on the back of her head in a manner reminiscent of the Dardenne brothers’ work. The Dardennes pose their camera behind their characters’ heads, asking viewers to imagine what might be going on inside, and here, we are granted the briefest of entrées into Dani’s stream of consciousness. “Stop it! You’re fine!” she shouts at herself, but the rapid-fire glimpses we get—of her family, of Dani running ever-deeper into a darkening forest—suggest otherwise. —Saul

Saul Austerlitz’s Substack Hope in the Dark covers culture, comedy, and more. His book Kind of a Big Deal: How Anchorman Stayed Classy and Became the Most Iconic Comedy of the Twenty-First Century is out now.