Judy Blume, Taylor Swift, and the Terrifying Threat of Young Women Mobilized

"Good girls" can be the scariest of all.

Judy Blume was a good girl. She married a nice man, like she was supposed to. She had children, like she was supposed to. She took care of them and the house, like she was supposed to. But she had this one thing she wanted to do, and it was naughty: She wanted to write books. She did it, on the side, promising that it wouldn’t interfere with her wifedom and motherhood. Then she went further, telling the truth in these books, these books that were for and about kids, explaining stuff that would happen to their bodies and weird feelings they might start to have when it came to sex. She used swear words, the way people really use swear words, against the advice of her publisher. Works like Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, Forever, Blubber, and Tiger Eyes became teen must-reads in the 1970s and ‘80s.

And this is how she came to be a banned author, pulled off shelves and admonished on television by Pat Buchanan. It’s also how she came to be divorced, and eventually remarried to the love of her life, and revered by generations of readers, particularly young women who were grateful for an adult willing to tell them the stories they needed to understand their own bodies and feelings.

Taylor Swift was also a good girl. When she began writing songs as a little girl, she also developed a desire to please as many people as possible. However much you and I wanted to please people (and I know I wanted this a lot), she wanted to please more of them, millions more of them, and it seemed she had an innate sense of how. Very soon she got straight As in a way that went far beyond school: She was pleasing major music critics far and wide and topping the Billboard charts, first with her teen country songs and then with her adult pop songs. She cultivated a peculiar kind of sway over her fans with the specific storytelling in her lyrics. Her songs, sung into your ear through your earbuds, felt like your best friend whispering her every truth directly to you. As she grew up, so did you. It was hard not to feel connected to her, even as her fame grew to mind-blowing proportions, especially, it must be said, if you were an Elder Daughter Type A.

And so we all ended up here, so many of us, looking to Taylor to understand our own lives, and to decide what to do or feel next. Which is what made it all the scarier for certain people when her unprecedented power reached a crescendo during the past year with her Eras tour, with some song-stagings that prompted speculation that she was promoting “witchcraft.” Related conjecture has wondered if her publicity-stoking relationship with football star Travis Kelce is a psy-op by the Pentagon to get Joe Biden re-elected as president.

My god, the power that young women, mobilized, actually wield. As book bans reignite across the country, and scare tactics target Taylor Swift, this is worth noting. When large numbers of young women are informed and mobilized, suddenly these nice, smart, overachieving women become the villains of Fox News and its ilk. When large numbers of young women are informed and mobilized, conservatives are scared.

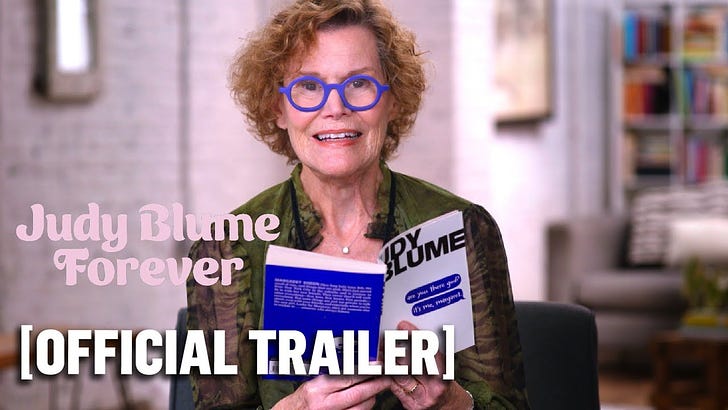

Blume didn’t set out to empower millions of young women, but her story demonstrates how one woman stepping into her own power, and sharing her truths, can change the lives of millions. Blume is the subject of a terrific recent documentary, Judy Blume Forever. The film covers her trailblazing books and their banning in the 1980s, along with their widespread influence, evidenced by interviews with the likes of Lena Dunham, Molly Ringwald, Samantha Bee, and Jacqueline Woodson. Blume was a suburban housewife and mom who discovered her talent for writing—particularly for speaking directly to adolescents, especially girls—and simply refused to put it down. She presented as sweet, pretty, and soft-spoken, a feminine ideal, even as she grew bolder in her depictions of puberty and teen sex, even as she faced shaming by right-wingers and bans. She was unwavering in her vision: Why bother if she was going to compromise? So dedicated was she to truth-telling, in fact, that she debunked the myth of Santa in Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, allowing for even further vilification.

As her career went on, it liberated her from a marriage she hadn’t really wanted and allowed her to branch out into adult fiction like Wifey, which was received as at least as much of a bombshell as her young-adult fiction had been. The 1978 book depicted a bored New Jersey housewife who finds new passion for life through an affair with a high school boyfriend. I discovered this novel in the 2000s when I was about to get married and become a New Jersey wife myself, and it affected me deeply. It’s not the reason I ended the engagement, but it was among several cultural influences that helped to give me the courage. So I suppose some patriarchal elements do have reason to fear Blume.

Swift has had similarly powerful effects on millions of young women, also by sharing her own truths. She was a suburban tween when she began writing music professionally, emptying out her diaries to narrate her life in song. Her records maintained a regular-girl narrative, full of talking on the phone late at night with boyfriends, fantasizing about marriage to forbidden loves, and pining for boys who insist on dating cheer captains instead of the girls who really understand them (who are, of course, stuck in the bleachers). Tellingly, Swift also copped to less-pleasant feelings of rage at duplicitous boyfriends and, especially, bullies and naysayers. She was a fully-formed heroine, and sometimes even an anti-hero, as she’d later dub herself on a very popular single.

The result was an almost fearsomely passionate fanbase who saw her as a best friend, a confidante, the only person who seemed to understand the drama of being a teenage girl, and to acknowledge it in a massively public way. As she has grown up, her fans have grown with her, and the subject matter has gone from first loves to adult-level betrayals, feuds, the joy and anxiety of real-deal love, and the anger and exquisite devastation of its end. She has never wavered in her message: Her feelings, and therefore her fans’ feelings, are allowed to be ugly and angry and uncomfortable, beautiful and transformative and swooning and embarrassing, and, most of all, big.

There is a telling quatrain in her new song “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” that fans have taken particular glee in screaming with her at her recent shows: “So tell me everything is not about me/BUT WHAT IF IT IS?/Then say they didn’t do it to hurt me/BUT WHAT IF THEY DID?” This is Taylor Swift’s argument boiled down. She is standing in for all of her fans and screaming: Maybe it is all about us. We matter.

Note that Blume and Swift share some key traits that seem to have contributed directly to their ability to “get away with” their truth-telling to audiences of young women—at least until their power became undeniable, and thus frightening to conservative forces. Both of them began as some of the most ignorable figures in American life: a suburban housewife and a suburban teen girl. They’re both white and pretty and well-behaved, overachievers and people-pleasers. They embody the “ideal” American girl and woman. They catered to an audience no one wants to take seriously, adolescent girls. This allowed them to be stealth bombs of feminism, a phrase I also used in my book Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted to describe the main character of Mary Richards on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, who fit a similar mold. Feminist messages go down easier wrapped in conventionally pretty, unassuming—and, of course, white—packaging.

And yet Blume dared to tell girls, through her fiction, the truth about periods, puberty, boobs, bras, masturbation, and premarital sex, all without a shred of judgement, scandalizing 1980s book-banners who would rather children knew about none of this, and seemed to believe that censoring Blume’s books would keep all girls innocent (or ignorant?) forever. Some of Blume’s works are still being banned today, along with books addressing more current issues such as LGBTQ+ identities and race.

Swift poses a different problem for conservative forces. Though her lyrics have gotten a bit more explicit than they used to be, the issue here instead is the way that her own brand of truth-telling has marshalled a fearsome army of mostly female fans who believe they are entitled to a voice in this world. Since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Swift has become more outspoken about her progressive-leaning politics, occasionally endorsing candidates, articulating a clear pro-LGBTQ+ stance, and, perhaps most fearsomely, encouraging her followers to register to vote. Given her left leanings, and the demographic of her audience, that alone could be enough to tip an election in Democrats’ favor.

The fear of Swift lays bare the real secret: It isn’t any policy stance that scares conservative, patriarchal forces. It is the rise of power in groups they can’t control, particularly in the very young women they’ve largely ignored until now, and who may even be angry enough to do something about it.

Speaking of empowered young women, I’ve got two more events left in my book tour for So Fetch, my cultural history of Mean Girls:

This Saturday, May 18, I’ll be at the Greensboro Bound book festival. At 4:30 p.m., I’ll be talking with local high school student Eve Hatcher Peters about Mean Girls’ lasting appeal with teens and its reverberations throughout pop culture.

Next month, at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, June 12, I’ll be at Book Soup in Los Angeles in conversation with Mean Girls casting director Marci Liroff, one of the stars of So Fetch, to get the inside stories on how she put together one of the greatest young casts in movie history. (She also did St. Elmo’s Fire, Footloose, Pretty in Pink, and Freaky Friday, so we can ask her about those, too!)

I’d love to see you if you’re in either of these places!

Thank you for this analysis, i had never heard of Blume before (pardon me, I’m French 😊)

I have to say at first read I didn’t agree with the notion that Swift is mobilized, especially given her silence in the past few months. But at second reading, it occurred to me that even as she’s not speaking or siding either way on the prevalent issue of our time, her fans are. I stumbled on a twitter page (I think) called Swifties for Palestine that has tens of thousands of followers. That goes to show how their identity as a “swifty” empowers them but also how much power she holds because there is a true belief that if her and other celebrities (Beyoncé for one) asked for a peace treaty, they might override Netanyahu himself.

My other disagreement would be on the notion that only the right is shaking in their boots. I think the increase in police brutality towards students and Hillary Clinton’s intervention claiming they don’t know what they’re talking about showed that left and right, no one wants the youth to think for themselves..

I love this essay, Jen, and now the connection between Blume and Taylor is so clear — and the phrase “stealth bomb of feminism” is so apt. I wish I could be at Book Soup!